Mass Datura - Wish Untitled

Mass Datura were initially formed as an outlet for Thomas Rowe and Joseph Colkett to channel their eclecticism, as the duo made a point of fusing their influences from grunge, alt-rock, doo-woop, blues and American folk.

With such a broad range of influences, as often happens, their pallet broadened even further, and the band grew arms and legs in the form of classically trained violinist and soprano Leanne Roberts, The Horrors’ guitarist Joshua Hayward, and Patrick Bartleet and Christy Taylor.

Their debut album, 2017’s Sentimental Meltdown, was a glam-tinged, colourful and chaotic slice of art-pop which was marked by a lack of discipline off-set by unbridled enthusiasm. Wish Untitled confirms chaos and irreverence are Mass Datura’s hallmarks, but they’ve progressed further down the timelines of history, choosing to plonk their Delorean in the car park of prog.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/07/album-review-mass-datura-wish-untitled/

The Blinders - Live From The Bottom Floor

We all know the feeling by now. The ‘I should have been…’ feeling.

Ruminations and regret about festivals or gigs that we’ve missed out on as the pandemic ripped through the world, cancelling event after event. Typically, and just our luck, the music industry has been hit the hardest (with the exception perhaps of live comedy).

Nadine Shah, a musician arguably in her prime, has had to move home because she couldn’t afford to stay in her flat in London now that the live scene has simply stopped and she has to rely on streaming revenue alone. We are all either twiddling our thumbs or, more likely, crossing our fingers for the rest of the year.

Yet, as the lockdown has lifted, the first tentative steps towards ‘normality’ can be taken.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/07/review-the-blinders-live-from-the-bottom-floor/

The Blinders - Fantasies Of A Stay At Home Psychopath

Released less than two years ago, The Blinders’ debut album Columbia was a rip-roaring glimpse into a quasi-parallel world, a dystopia which nonetheless appeared eerily familiar.

Subtle references to the twin disasters of Trump and Brexit abounded, it both a timeless piece of work and a capturing of the zeitgeist.

Now we find ourselves further ensconced into this dystopia than even Messrs Trump and Johnson could surely have envisaged; once regarded as part of delusional fiction, facemasks are (due to be) a common sight in day-to-day life, while the powers that governments across the world have granted themselves leave progressives despairing still more, to say nothing of the non-political issues facing the world.

And so, whilst it’s unlikely to be a moniker they truly enjoy, the trio from Doncaster-via-Manchester continue to release prescient music.

Paul Weller - On Sunset

It’s fast becoming one of the more common clichés in British rock, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth highlighting: Paul Weller has been on a rich vein of form for fifteen years, his solo career redeeming itself (at least in his own eyes) over the course of the 1990s before becoming slightly rudderless at the turn of the century.

Buoyed by the success of As Is Now in 2005, with an energy and vitality that had been missing, Weller has since felt no obligation to return to the mod/soul formula he long since mastered.

On Sunset is a reaction to his last album – the reflective, pastoral True Meanings. Where that 2018 effort was restrained and simple, this new slice reveals itself to be more of a challenge, but with better rewards over time.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/07/album-review-paul-weller-on-sunset/

Pottery - Welcome To Bobby’s Motel

You know with a title such as this you’re going to be entering a world unlike any other.

Montreal’s Pottery gave us some glimpses into their heads on last year’s slightly less-mysteriously titled EP No. 1, but while previously it was a work in progress, here we have a definitive look.

First impressions? Welcome To Bobby’s Motel is likely to be a sweaty place. Never sitting still, we are welcomed via a largely instrumental title-track which, at only two minutes, may be brief but squeezes a lot in. The guitars have a striking balance between glam and art rock, while the bass takes prominence in the mix (as it will throughout much of the album). There are some distorted vocals alongside spluttering synths which act as smeared narration and return later in the album.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/06/album-review-pottery-welcome-to-bobbys-motel/

Bob Dylan - Rough And Rowdy Ways

The greatest troubadour in town is back.

He also turns 80 next year. He won’t be the first of the 1960s generation to do so, but it will feel significant – albeit probably least of all to Bob Dylan himself, as he’s been ruminating about death for over twenty years.

Ever since the ‘return to form’ album Time Out Of Mind, the spectre of Father Time has been prominent in Dylan’s work. So, unsurprisingly, it plays a big part on Rough And Rowdy Ways, his 39th studio album. Yet, where he once addressed mortality, here he takes a step back and views how the world has changed and how it also repeats itself.

The best example of this is ‘Murder Most Foul’, released as a 17-minute comeback single (remarkably his first No.1 on the Billboards), the lyrics commence at the assassination of JFK (the titular murder) and thereafter become a potted history of pop culture. It’s quite an undertaking, and wisely the track is left for last on the album. As insightful as it is (and worthy of its run time), for any listeners opting to succumb to Dylan’s genius for the first time it would be off-putting.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/06/album-review-bob-dylan-rough-and-rowdy-ways/

Jehnny Beth - To Love Is To Live

When Camille Berthomier (for it is she) cited her band Savages as a ‘prison for creativity’ a few years ago, her comments were received with some raised eyebrows. Whilst the band’s oeuvre could certainly be categorised as post-punk with little resistance, that both albums were nominated for the Mercury suggested a tinge of artist pretension.

Regardless, the time it’s taken to release her debut solo album (four years) was a clear indicator that it would be a sonic departure. Despite a few extra-curricular distractions (collaborations with Julian Casablancas and Gorillaz, as well as her own online chat show), it feels like this album has been coming forever. However, it’s now plain to see that Beth has very obviously poured her heart, soul and mind into it, with a breadth of soundscapes that make her much more difficult to categorise.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/06/album-review-jehnny-beth-to-love-is-to-live/

Orlando Weeks - A Quickening

The Maccabees were a rarity among indie bands; defined by their honesty, the group announced their split and a series of farewell gigs three years ago when they were at (or near) the top of their game.

Two successful but relatively run-of-the-mill albums provided a confidence to push their own boundaries on their masterpiece, the Mercury-nominated Given To The Wild. Serious muscle and scope was added to the usual sound whilst broadening the soundscape to be more ethereal and fragile.

After 2015’s Marks To Prove It, an inferior (but no less successful) sibling, the quintet were surely next in line for the headline slots. To their immense credit, instead the bandmates felt they had run their course and went their separate ways.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/06/album-review-orlando-weeks-a-quickening/

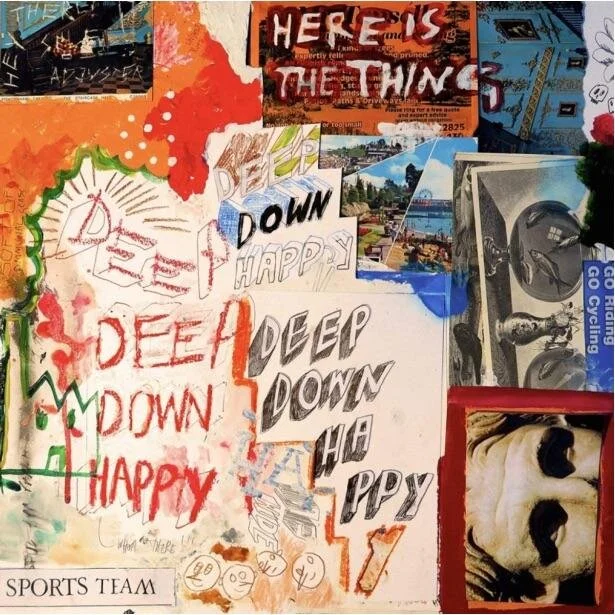

Sports Team - Deep Down Happy

Sports Team have been, up to this point, defined by their live sets, crammed as they are with wilful freneticism.

Whilst the songs themselves are not exactly disenfranchised youth anthems, they’ve given a voice to a jaded and confused (and salivating) generation. Their gigs have been testament to this, Alex Rice flouncing joyfully around the stage like the lovechild of Jagger and Morrissey.

Meanwhile, along the way they’ve released a string of relentlessly upbeat, catchy singles, all of which have reflected their modus operandi in some way or another. As such, this debut album is both successful before it’s even released, and sometimes suffers from over-familiarity (despite the mystifying omission of ‘M5’).

The paradox is very apparent; chirpy, guitar-led pop that takes its lead from the art and Brit genres is a formula that rarely fails. The music doesn’t break any new ground, yet is driven by an enthusiasm that only youth can provide. ‘Here It Comes Again’ features Coxon-esque guitar work beneath the snappy, ever-so-slightly distorted vocals, while ‘Going Soft’ leans heavily on a lick that echoes The Jam’s ‘English Rose’.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/06/album-review-sports-team-deep-down-happy/

Interview - Hinds’ Ana Garcia Perrote

When I spoke to Hinds’ Ana Garcia Perrote at the end of April, the immediate effects of the coronavirus pandemic had been felt close to home: “My parents are both doctors,” she told us. “Ade’s (Martin, bassist) parents both got it and are both fine. Carlotta’s (co-vocalist and guitarist) mum got it, but she didn’t have any symptoms. It’s all good, but it was a lot to take in.”

Amidst this very personal turmoil, the band’s new album The Prettiest Curse felt the effects too, like so many given a later release date which will, finally, come around this Friday (June 5th). Although it was frustrating to delay the album’s release, it was an easy decision; “When we release albums, and for most other people, it’s a very exciting moment that you can celebrate and be happy about,” Perrote said. “A lot of work behind the scenes, which in this case has taken over a year, sees the light. It’s like your birthday party or something. Then, suddenly, it didn’t feel right to talk about it, because everyone was going through a lot. It was very scary.”

Hinds haven’t been idle during the wait. Like many other artists the quartet have taken to the internet to engage with fans, but in addition to performing, they have also delivered a sequence of tutorials, partly for variation but also to inspire their fans: “Obviously the live things we do, where we play it separately then put it all together, that’s really fun but more for people to watch.”

Hinds - The Prettiest Curse

Reflected by the spring easing its way into summer, the light at the end of tunnel shines a little bit brighter.

Whilst society isn’t quite settled into the ‘new normal’ just yet, with gargantuan question marks still hanging over the future of the music industry, at the very least the first wave of the apocalypse is over.

Originally scheduled for release in April, Hinds’ third album The Prettiest Curse is now set for June 5th, come hell or high water (which, in 2020, have to be regarded as possibilities). Indeed, when I spoke to co-vocalist Ana Garcia Perrote from her home country of Spain during the lockdown, she was adamant: ‘It’s definitely coming out in June. Worst case scenario, if we’re still in lockdown or something, we’re still going to release’.

Such are the earth-shattering effects of the pandemic, the worst-case scenario is here as both the UK and Spain continue to live in this perpetual lockdown, but The Prettiest Curse is the shining explosion of joyous pop that people will need. A real shift from Hinds’ quasi-lo-fi sound, the album is stocked to the gills with pop hooks and colourful imagery that’s reflected in the music.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/06/album-review-hinds-the-prettiest-curse/

Tim Burgess - I Love The New Sky

There have been suggestions that Tim Burgess should receive some form of accolade for bringing music fans together during lockdown, ideas posited including Godlike Genius at next year’s NME Awards.

There’s no doubt his Twitter Listening Parties are a wonderful initiative, encompassing a huge range of album choices, some of which have acted as moving tributes to Little Richard and Florian Schneider, and others that have given newer artists the opportunity to showcase their music to a wider audience.

Owing to the organic and amateur nature of the venture, ideas are allowed to blossom; the Listening Party website directs viewers to independent record stores, and there’s a full festival on the way. However, there’s a strong argument for Burgess to be the recipient of some form of accolade even without these listening parties.

Now on his fourth decade in the business – with thirteen Charlatans albums and this, his fifth solo album, under his belt – Burgess is clearly driven by a passion for music, equally demonstrated by his forays into running labels and writing. His solo albums have been notable by their eclecticism: I Believe was quasi-Americana; Same Language, Different Worlds was pulsing electronica; Oh No I Love You featured slow-tempo indie. Now, Burgess has taken things up a notch by recording an album that offers huge sonic variation from its first track onwards.

https://www.live4ever.uk.com/2020/05/album-review-tim-burgess-i-love-the-new-sky/

Interview - Tim Burgess

Some people are gluttons for punishment.

Whilst a great number of us have been making the most of this free time, the world still turns in our absence, and musicians still have work to present. Tim Burgess is one such soul, and while his Twitter Listening Parties are taking up most of his time (more on those later, inevitably), his fifth solo album I Love The New Sky is released at the end of the month too.

It’s ostensibly a follow-up to 2018’s As I Was Now, but the two records couldn’t be more different. For one thing, their gestations had completely different lifespans; Burgess sat on the previous album for the best part of a decade, whereas the new one was recorded in just a year. “As I Was Now only took about five days and I released it unmixed,” Burgess tells me in an exclusive interview. “And some of it was unfinished, but I just felt it was a really nice release. It was a good story and a nice archival release for Record Store Day.”

Tim is talking to us after a couple of false starts; “I was going to speak with Live4ever at South By Southwest. That was the first thing that disappeared. It’s amazing though, we would have been talking about completely different things.”

The new album is his most eclectic album to-date, taking in avant-jazz, music hall and even woozy house music, and while his recent work has been more collaborative in the songwriting sense (2012’s Oh No I Love You was written with Lambchop’s Kurt Wagner; in 2016 he co-created Same Language, Different Worlds with Peter Gordon), on I Love The New Sky, Burgess wrote all the songs and then took them to various peers to gauge opinions:

“I wrote the album by myself but in no way could I have made it myself. The collaboration aspect with this album came in the studio with Nik Void (Factory Floor), Daniel O’Sullivan (Grumbling Fur) and Thighpaulsandra. Not all necessarily at the same time. They’re people and friends who all understand the aesthetic that I was looking for. It was a sort of Canterbury, 70’s kind of sound mixed with New York vibe, some very LA Sunset Boulevard. Some dreaming songs and some self-referential songs: ‘Timothy’, ‘Only Took A Year’, ‘I Got This’…very personal songs, and they helped me furnish the songs that I brought in.”

Burgess’ preparation allowed ideas to flourish in the studio, for example on disco-Floydian ‘The Warhol Me’, which Burgess says, ‘started off as a guttural punk idea’, before, ‘Nik Void added this incredible modular synth that took it into New York territory’. Elsewhere, ‘Sweet Old Sorry Me’ has an intentionally mid-1970s vibe (‘I was thinking Steely Dan and ‘Boston Rag’ in particular, I wanted an aspect of great studio musicianship in the album too’), while ‘I Got This’ was a tricky nut to crack, but eventually made the album to level it out at twelve tracks, as he explains: “We spent a long time getting the sounds right. I wasn’t sure but it was the last song, and the more it grew the more I really thought, without sounding corny, that I’d got this. It was twelve tracks and I didn’t want any to not be on the album.”

At surface level, ‘Timothy’ (the song) is the most obviously self-referential, but don’t be fooled. Burgess is coy about the song’s theme, its ‘decoys’, but whether or not the song is autobiographical is ultimately immaterial, although The Charlatans’ frontman concedes that it represents him: “The thing that I really love about that song is that it’s low-key. You might not notice it straight off, but it’s there and it is catchy but not in your face. That kind of reminds me of me really! I’m catchy, but not in your face.”

One thing is obvious when talking to Tim Burgess: that a love of and belief in music informs everything he says. This passion has been welcome during the lockdown. As you probably know, Tim is the man of the hour thanks to his Twitter Listening Parties – a distraction from the general despair of what’s happening in the world right now, but also a chance to revel in our shared physical situations.

From its beginnings on day one of lockdown (Some Friendly by the day job), there’s now talk of getting real rock royalty involved; “Mick Jagger liked somebody else’s tweet,” Tim says. “He responded and said he had been getting involved and watching social media.” Even if the Glitter Twin doesn’t grace us with his presence, there are plenty more parties to come – a now-lengthy list including Kevin Rowlands, The Specials, UNKLE, Joy Division and Nadine Shah among countless others.

“We’ve got all of May and the first two weeks in June booked up, there’s also still plenty to come. Every day I’m trying to book three or four people in the middle of doing everything else as well. Today’s been about Rufus Wainwright and Ian Astbury, so my head’s in that at the moment. You have to offer everybody a couple of dates. I know people are quite quiet, but you have to offer everyone a couple of dates, then you don’t hear back from them for a couple of days. You’ve got to keep everything pending.”

It quickly became apparent that such an ever-evolving idea was beyond the capabilities of one man. “We adjusted pretty well at the beginning. Within three days I had four people working on it; one person on the scheduling with me and then two guys doing the website, on a rewind in real time (all parties are available via this website). I’d never met them before and they don’t know each other either, so it’s just from the pure love of seeing what I was doing. There’s now four of us involved.”

With the organic nature of the venture, and the modes of communication open and instant, middle men are broadly cut out. Very much in line with the principle of the venture, people are either invited or encouraged to participate. “There’s times when I feel like I have to ask somebody even if I don’t think they’ll do it, but I have to let them know that I’m asking because I’d hate to think they weren’t being asked,” Tim explains. “There’s all these emotions involved in it.” Nor would anyone be refused entry: “I’m open to all genres. It’s really an open door for everybody, but the main thing is that they really want to do it and that they can put on a good performance, if that’s the right word. I’m just making it up as I go along! There’s certain people that I really wanted to get involved, people who I consider a little bit mysterious who make incredible music, like Julia Holter and Ariel Pink. I really wanted Quelle Chris to do Everything’s Fine, a Chicago hip-hop record that I really love. There’s a dialogue but nothing confirmed. Duran Duran came in the other day, someone suggested that with the idea that I may not be interested but of course I am.”

It’s been so successful that it could readjust music promotion altogether. Other listening parties have popped up – in the process re-creating what will surely be the only thing missed from the festival experience in 2020: schedule clashes – and sooner or later the industry is going to take the idea for themselves. Burgess isn’t worried: “There is that, but it has to retain…I’ve had so many people telling me how it could be done via Zoom, or it could be done on Facetime Live or stuff like that. I’ve had to tell everybody, ‘I love your idea, but it’s not the idea that I’m doing’. It’s far more simplistic, far more about the record and far more about doing it without cameras on you.”

“They can use that idea and do it their way if that’s what they feel like doing. Dave Rowntree chose Parklife; Bonehead chose Definitely Maybe. When it becomes people wanting to do their new album, which is out in three weeks, ‘Have you got space in seven days to preview it?’, that’s when another level of complication comes into it. I get asked about that all the time, and if ends up going that way it has to be a slow process or else people are going to think it’s horrendous. It would just ruin it.”

The Tim’s Twitter Listening Party website doesn’t just act as a calendar. The site is regularly updated with links to independent record stores in an attempt to encourage participants to support them, as well as a list of recommended music reading curated by Dave Haslam and Pete Paphides, among others. Seemingly every time you visit there’s a new page, and it’s fast becoming a barometer of how people are engaging. “The music industry can adapt and things are happening, but with all the streaming things, I’m feeling bad about my fellow musicians that are only getting paid tiny, tiny fractions of an amount even though they’re raising so much,” Burgess tells me.

By ‘the streaming things’, Burgess is referring to the disparity of remuneration from the major streaming services between performer and labels. With live music off the agenda for the foreseeable future, and the cancellation of Reading & Leeds acting as the final nail in the coffin for the 2020 festival season, performers are more reliant than ever on other sources of revenue. Tim Burgess brought the plight to a wider audience and is conscious of how things may play out without action: “It went from musicians not really making money from records because of streaming, so it’s all about live and merch. I don’t think anybody really feels like they need a t-shirt with some tour dates on the back at this moment in time, so merch has fallen off a cliff. The focus is going to go on streaming sites because no-one can play live.”

Either Burgess was keeping things under his hat, or perhaps this was demonstrable evidence of how quickly things can develop in the Twitter Listening Party world, but a few days after our conversation he announced a festival (featuring John Grant, KT Tunstall, Pins, The Shins and Boy George) in conjunction with the Broken Record campaign. As easy as it is to become blinded by the numbers involved, via the breakdown of streaming payments Burgess, as he so often does, makes the facts easily digestible: “All I think is that there’s about 130 million Spotify users who pay about a tenner a month. It’s an incredible amount of money. Somebody on Twitter said something along the lines of, ‘For all the work I’ve been doing, they’d like to buy me a cup of coffee’. It would take a million plays on Spotify for the price of one coffee.”

Western societies may now be finally taking their first tentative steps into a post-COVID world, but the future is still very uncertain for the music industry, and that looks set to be the case for a considerable amount of time. What started as a fun idea is blossoming into a movement. Burgess is, perhaps inadvertently, harnessing the passion of music lovers into something positive as we confront these troubling times head on:

“I am conscious of the future of music, bands not being able to be sustainable. There’s only a few that can play Brixton Academy, but that’s only just about sustainable when you get to that level. Below that, bands can only be part-time and that’s not good for the future of music. It has to be a bit fairer.”

Wise words from music’s new patron saint.

Mark Lanegan - Straight Songs Of Sorrow

Death is the one thing that all mankind has in common, yet for most of us it’s a taboo subject – understandably, as it’s not a traditional topic of dinner-party (or Zoom) conversation.

Human beings are so fearful and arrogant that the thought of a world without loved ones or ourselves is judged to be best handled with copious denial; Mark Lanegan is not a believer of such principles.

While never lackadaisical, Lanegan is on a rich vein of creative form: Straight Songs Of Sorrow is his second album in seven months, an accompaniment to his memoir Sing Backwards And Weep, released in late April. Whether or not listening to the album intrigues you enough to warrant reading the book, it’s a wholesome piece of its own.

The first three tracks set such a precedent that it’s ultimately difficult to be beaten. As before, Lanegan demonstrates that he’s equally comfortable with moody electronica and simplistic acoustic. The opener, ‘I Wouldn’t Want To Say’, is one of his more overt forays into the former, with crowded production and a fast pace that demonstrates the urgency of thoughts on death, ruminating that he’s running out of time. ‘Swinging from death to revival’, Lanegan utters in his trademark growl, ‘How many more years will it be before the end of this sad machine?’. The melancholy is almost suffocating as an incessant bell (which reoccurs through the album, presumably for whom it tolls) sets the tone for things to come.

In contrast, ‘Apples From A Tree’ (featuring Lamb Of God’s Mark Morton) is an exquisite, finger-picking acoustic track, supplying the hope that was lacking in its predecessor; death is described as ‘taking flight’ amidst what is essentially an ode to his wife, Shelly Brien. She pops up on the following track ‘This Game Of Love’ to form a duet with her husband. Using the dichotomies of heaven and hell with loneliness and companionship, it has a bleak feel, but the obvious love between the two singers elevates it.

Thereafter, the songs all fall within the same three categories: despair, optimism and melancholy. ‘Ketamine’ refers to Lanegan’s past excursions of attempting to score after gigs in Europe, with the bell tolling once more. ‘Churchbells, Ghosts’ is akin to a Play-era Moby track, striking piano and pulsing heartbeat holding things together whilst Lanegan wails. ‘Stockholm City Blues’ is a string-led ballad, in itself an impressive musical accomplishment as the layers of music take turns in leading, but is a tortuous listen.

‘Hanging On (For DRC)’ is another acoustic paean, this time to his friend Dylan Carson, genius progenitor of, ironically, drone metal. Fortunately, Carson isn’t dead so the track is whimsically uplifting. No less a luminary than John Paul Jones shows up on the electronic blues of ‘Ballad Of The Dying Rover’, providing rhythm to the sometimes overbearing ambience that forms much of the album.

And on (and on) it goes. The album clocks in at an hour, this working against it by exposing the lack of contrast in the song templates. There’s an excellent album buried amongst the maudlin maelstrom – some judicial editing wouldn’t have gone amiss.

#Broken Record - Interview with Crispin Hunt (2/2)

There are many bitter ironies about this new world we inhabit after COVID-19 entered our lives.

The saddest of all is, of course, that those best placed to treat the virus are those that have the greatest exposure to it, our NHS staff and care workers bravely soldier on (if you’ll forgive the disingenuous war analogy one more time), doing their best, which is all any of us can ask.

Further down musicians are, perhaps unsurprisingly, showing themselves to be increasingly creative. Live-streams on Instagram and Facebook were already commonplace, but in the last two months the rise in this content has been meteoric. The sight of artists in their own homes (fortunately not against a backdrop of educational tomes) has already become the most familiar one of 2020. This fascination surely peaked during the Global Citizen ‘gig’ as Elton John inadvertently provided memes for the rest of the year whilst The Rolling Stones, always the savviest cats in the game, decided that 50% of the band performing would suffice.

Every night Tim Burgess hosts listening parties on Twitter, Noel Gallagher and The Libertines (among others) are taking the opportunity to clear out their cupboards, releasing treats in the form of demos or live recordings. Radiohead have taken things even further, putting entire gigs from their career on YouTube.

For the Jaggers and the Gallaghers of this world, these are little more than (appreciated) gestures of good will. For those further down the food chain still, the situation is much more severe. Their main source of revenue has simply stopped, with no clarity as to when, or in some cases if, it will resume. An ever-evolving beast, the music industry has long been financed by live performances. Gone are the days when an artist or band could get by on record sales alone.

Despite the rebirth of vinyl, sales of the physical music product have fallen through the floor because of streaming services. For £10 per month or less, the consumer has access to virtually the entire recorded history of music. Unfortunately, owing to the antiquated contracts recording artists are bound to, the creators receive negligible financial reward in return.

Via Spotify, the market leader, an artist can expect to receive £0.0004 per stream. It takes 2,500 streams for them to earn £1 – figures, whilst more lucrative, that are comparable across the various streaming services. In early, April Tom Gray, a director of PRS, tweeted some comments and stats outlining this very problem. In summary, even before the pandemic, musicians were in trouble. Gray’s tweets made over a million impressions and has transformed a conversation into an awareness campaign: #BrokenRecord.

Crispin Hunt, now Chair of the British Academy Of Songwriters, Composers And Authors, knows better than most about the dire straits the industry is in. A long-time advocate of parity for songwriters, Hunt knows immediate action is required.

“We really need to address this, it’s urgent,” he tells me. “It’s been on the agenda for a very long time, but I think now that people are really struggling to make rent yet are selling millions of streams we need to start asking questions. What’s clear – and has been exposed by the lockdown – is that musicians can no longer continue to subsidise the music industry with their earnings from live performances. Live is great, but it’s a separate issue. By musicians I mean songwriters, session musicians, performers, artists, producers – they should be able to sustain themselves on recorded music, because recorded music is now making an awful lot of money.”

A lot of money indeed, but the record labels weren’t so slow to react when streaming started to establish itself as a force in music consumption. “The labels did the sensible thing when Spotify first turned up,” Hunt explains. “Whenever a new platform turns up, they say, ‘you can have our catalogue licence, but we want 5% of your company too’, so they all had varying small percentages of Spotify. In my understanding, the cost of those shares was originally something around £200,000, which is the price of a half-decent artist to a major label. They sold part of their shares recently for many tens of millions of pounds. They’ve done very well out of it.”

This may conjure up images of Machiavellian record labels as ruthless corporate pigs, quaffing brandies and smoking cigars, caring only about lining their pockets, but the reality is, as ever, more complex: “The people who run the large labels are forced to answer to these shareholders and large hedge funds, so they can’t behave in a way that suits the business they’re in, which is art,” Hunt says. “They’re forced to make decisions which aren’t artistic, but commercial ones. Music has suffered for that.”

This hasn’t stopped streaming services adapting their offerings: all streaming services offer playlists that are designed to appeal specifically to the user. This may appear to be an act of kindness, in fact it’s nothing so altruistic. It’s all part of the game, and it’s not just the artists that are losing out. The curation model that streaming services use is having a detrimental effect on radio: not bound by having to cater to a specific audience (on a grander scale), record labels approach the streaming sites first, which in turn reduces the requirement for radio stations.

Hunt elaborates for Lme: “They (streaming services) compete on curation, but that means that their behaviour becomes less like a shop and more like a broadcaster. The law is questionable about whether streaming is…it’s all defined as a sale. It pays as if it’s a sale, so it goes to the record company and then they pay via contract. But really, if you go on to Spotify and say, ‘I want to listen to Arctic Monkeys’, that’s a sale. You’re going into a shop and choosing something. But if Spotify plays you something by Arctic Monkeys as part of their early morning playlist that’s a broadcast, and it should pay like a broadcast.”

Further muddying the waters is the legislation for YouTube. A few exceptions aside, you may have noticed those acts performing online recently have been doing so on Instagram and Facebook. Whilst the instant access and interaction for fans is undoubtedly the primary reason, there are also complexities over remuneration from the video giant. Like streaming, the original contracts are now somewhat archaic, as Hunt explains to me:

“When WIPO (the World Intellectual Property Organisation) gave rights and broadcasts to performers, so that the players get paid when their music is on radio, there was a big argument whether it should include audio-visual works, i.e. films and TV shows. That was considered a step too far. They did a deal that said they would give musicians some money from broadcast (radio) but not from TV, where music is trapped inside a piece of video. Of course, nowadays everything is audio-visual, and on Facebook and YouTube.”

In a nutshell, artists (of all shapes and sizes) get even less money from YouTube than they do from streaming services, yet YouTube is free for the consumer and will therefore be more readily utilised. Once again, the lockdown has brought this further under the microscope. “The streaming services are all competing with each other, and the trouble is they’re all competing with YouTube, which is free,” Hunt says. “Until YouTube pays properly, they will all say, ‘until YouTube start paying properly, we can’t get people to pay £12.50!’. In addition, as the audio-visual model is becoming more catered to streaming, the creators don’t receive remuneration for their work being played on BBC iPlayer. If you’re watching Eastenders online, whoever is on the Queen Vic radio won’t be receiving payment as you watch.”

The further you delve into all this, the bleaker it becomes. But there is hope: last week, the Beijing Treaty was enacted by over 30 countries. The treaty grants performers economic rights for audiovisual fixations, i.e. performances on YouTube. It still needs to be ratified, which will take time, but presuming that takes place it will level the playing field. It may also encourage streaming services to adapt accordingly. The market is competitive, but none of the platforms have adjusted their prices in the last few years for fear of driving consumers away.

“There’s two ways of dealing with it,” Crispin believes. “One is that you rejig how the music gets divided – the ten quid that gets divided at the moment goes: £3 Spotify, £1.20 to the songwriters and the rest to the record labels. I think, personally, that it needs to go four ways: 25% to the platform, 25% to the song, 25% to the singers and 25% needs to go the sellers. The other answer is to raise the price. You either divide the money fairly so that it’s more proportional, or you raise the price.”

Consumers may baulk at a price rise, but a slight increase in the price of access to virtually every piece of recorded music in history will ensure that the scope and breadth of what is available doesn’t run out. “Interesting fringes and new music used to survive because people got into it and they bought it,” Crispin continues. “That nourished whatever the genre was so it could grow. That’s exactly what happened to hip-hop/R&B, which is now the dominant pop format. I don’t think the ‘new’ hip-hop/R&B would get the oxygen to succeed under the current structure. At the moment, no matter how great and popular you are, you’re kept submerged under the surface because the winners take all. It’s a zero-sum game by design.”

“Streaming services will say, ‘you’ve got to put it in perspective, you’ve had a million streams’. If it was one play to 20 million people on radio, you’d only earn twenty quid, whereas with us you’d earn fifty quid. But a million streams is a million people choosing to listen to your music, you’ve got to be able to buy a weekly shop on that. The income from live should be complementary to what you make for your recordings. It’s not an advert for your gig.”

“Everything online is distribution now. There’s no such thing as promotion, apart from the music itself because it’s really popular, and everybody else is making a lot of money from it, like YouTube and Google and the major labels. I think that money needs to go back to the people who make it.”

It may seem immaterial in the greater scheme of things, but as hard as it is to believe right now, life will go on. Yet with large gatherings off the agenda for the foreseeable future, music fans are going to need the creators more than ever. The time for change is now. These changes don’t need to be wholesale but as a starting point, Hunt is adamant: “Streaming needs to be reconfigured. It needs not to be paying as it did via contracts that are still, basically, based on pieces of vinyl. We need to completely rethink how the money that is driven by musicians gets back to musicians. This will, of course, affect the industry, but it will affect it positively, as it means there’s a flourishing and holistic future for music.”

“We should all be able to benefit from the fantastic advantages of online. That was what was promised, but we’re now at the point where we have to make sure those promises are kept. What concerns me is that the people who make all of the brilliant stuff that we all enjoy, and which nourishes our lives, just aren’t getting a fair share of the money generated by the stuff they create. It’s the same for all creatives. We need to re-balance that for the sake of society.”

“There are so many questions being asked about what the new normal will be when we’re out of lockdown. It cannot go back to the bad old days.”

Interview - Crispin Hunt (1/2)

In part one of my interview with Crispin Hunt – one-time frontman of the Longpigs and current Chair of the Ivors Academy – we look back on the Britpop peak of the band upon the re-release of their debut album The Sun Is Often Out…

Britpop is now regarded with disdain by some and while it’s fair to say it had negative aspects, it was also a time of inspired creativity and cultivated enthusiasm. Unlike previous musical movements, the three ‘big hitters’ – Oasis, Blur and Pulp – were three very different types of band, and further down the pecking order the only uniting factor for those concerned was that they all had guitars.

For the nineties, the term ‘Britpop’ began life in ’94, but what are now recognised as the defining albums of the era were all released by the tail end of 1995. Not willing to let a cash-cow die, the ‘second wave’ brought many more acts into play, including a four-piece from Sheffield called the Longpigs.

Yet the moniker never sat comfortably with this band; “We always thought we were an art-grunge band,” Crispin Hunt tells me. “We didn’t like being called Britpop. We wanted to be Pavement. We were a noisy, heavy band and that was difficult in the 90s. It was an extraordinary time with Cool Britannia, and the world was looking at London and British music. It was a heyday, if you like, and really good fun to be on the radio and in London at the time when the world was listening to the radio in London! That was amazing, but it does mean that everything got packed under the title of Britpop, which was always a pretty unsavoury aim for anything.”

Longpigs’ debut album, The Sun Is Often Out, contained a string of successful singles including ‘Far’ and ‘On And On’, which also reached the Alternative U.S. Top 10. In the two-and-a-half-decades since its release, it’s gained cult status and is now being reissued on its silver anniversary. “I’m glad that it’s still got a life twenty-five years later and people still want to listen to it, which is exciting,” Hunt tells me, although typically for a creative, he won’t be revisiting it himself: “I find it impossible to listen to, because with your own work all you hear is the mistakes. You don’t hear the whole thing so it’s difficult. But sometimes you go in somewhere and it’s on and I go, ‘This is actually really good’.”

Despite the success of the album Hunt and his bandmates, including guitarist Richard Hawley, had the classic indie band outlook: “I grew up in the days of the Stone Roses and Echo & The Bunnymen, and we thought they’d sold out if they got into the Top 20. So for us it was almost deliberately cool to fail.”

Yet failure was not on the agenda: following the album’s success, things moved very fast. “We did amazing things: we played with U2 when they were doing massive tours, it was an extraordinary thing. For a little bit we were better known in the States than we were here. It also meant that it was a long time between records so when we came back, we had a very short amount of time to write the second album.”

You’ll be familiar with this part of indie tale; ‘The Difficult Second Album’. The theory goes that bands have all their lives to write and perfect their first album and a few weeks to write their second. The quality levels dip as the artists struggle to maintain their standards. Such a fate befell the Longpigs, but rather than writer’s block affecting the work, they were instead victims of their own success.

“We sort of finished doing The Sun Is Often Out in the UK and Europe, and we had a really good time doing it, then On And On became a big alternative radio hit in the States,” Hunt explains to me. “What we probably should have done was say ‘no’, stopped and gone to work on the second album then. Instead, you’re being pressured by your record labels, and also the thought of doing two years touring America is pretty attractive.”

“When we came back in ‘98 we were in pieces after five years of constant gigging. It’s the same amount of time as The Beatles spent constantly gigging and then they stopped, and I understand why they did. We were frayed at the edges a little bit. You go on to the tour bus and it starts like Summer Holiday, but two weeks later it’s like Das Boot. You’re really close and uncomfortable. But it was an amazing journey and a fantastic time.”

“So when we came back, we had a very short amount of time to write the second album. I always thought Mobile Home was brilliant lyrically but not as engaging melodically as the first record, if I’m being totally honest.”

Sadly, after the second album failed to hit the same heights as their debut, the Longpigs disbanded. “I think it was just the right time,” Hunt recalls. “It burnt very brightly at both ends and then it just burnt out, frankly, which is fine.” Yet twenty-five years on, The Sun Is Often Out is more than worthy of re-evaluation, as demonstrated by the clamour for this re-release. “I’m very flattered but apparently there was an awful lot of demand for it, so it’s been put out,” Hunt concludes.

“What heartens me now (Hunt now co-writes songs for numerous contemporary artists, including Florence & The Machine and Jake Bugg) is that I get a lot of really cool young bands who are coming in and saying, halfway through a session, ‘We loved your band’.

“We used to cite Television as a group that nobody had heard of but were really cool.”

It’s fair to say a lot of bands now see Longpigs as a similar influence.

Ist Ist - Architecture

Spoiler alert: this record is unlikely to lift your mood.

If you listen to music as an act of escapism (we all do), but also for its capacity to feel swathes of joy rather than recognition or melancholy, Ist Ist are not the band for you right now.

The Mancunians have taken their time over this debut. Operating since 2015, the steps taken to get to this point are familiar yet different: as most bands do, the four-piece cut their teeth on stage, but had both the gumption and the nous to release limited edition CDR bootlegs of these gigs which financed their early recorded work in the form of EPs which then, in turn, paid for Architecture.

Thinking further outside the box, the band have drip-fed tracks from the album over the last few weeks – similar to the traditional format of singles, but for every track. Whilst the approach is risky, the way the music industry is moving it was only a matter time before someone went the whole hog. Such clarity of thought and focus is apparent in the music itself, and is there from the off.

Opener ‘Wolves’ is full of foreboding, dystopian science-fiction with hairpin-tight notes and high-hat driven drums. Aptly, as the track recalls Suede’s magnificent ‘Introducing The Band’ (in tone rather than tempo), Adam Houghton’s vocals fade away whilst the rest of the band do their thing in creating a righteous funeral procession. The icy ‘You’re Mine’ is packed with grandiose guitars and whip-crack drumming, and lyrics such as, ‘you need to reassess and understand the essence of life that we possess’, should give some indication of where we are.

On that basis, it will come as no surprise to read that Joy Division are Ist Ist’s spiritual forebears, but perhaps not in the way you would think: Houghton’s striking baritone vocals undoubtedly channel Ian Curtis, but ‘You’re Mine’ and ‘Silence’ are two of a number of tracks featuring loping basslines that wouldn’t be out of place on Closer or New Order’s pre-1993 output.

Silence also echoes White Lies (specifically the track ‘Death’) in the guitar tones, but is the sort of track that band always wanted to write but weren’t dark enough of soul. Likewise on ‘Night’s Arm’ Houghton sounds uncannily like Harry McVeigh, but again the layered guitars and depth of the song supersede anything that band have done. Best of all is ‘Slowly We Escape’, another funeral march but traditionally organ-led until it explodes excitingly into life, barnstormingly rock out and then fade out. Think Interpol doing Muse’s ‘Knights Of Cydonia’.

The comparisons with other doom-laden bands then are obvious but valid, yet it’s not all dark melancholy. Despite the title, ‘Black’ is some form of love song with more hopeful lyrics (‘I can make the seas part for you’) and strides epic commerciality very well, smacking of ‘crossover hit’. But largely, desolation is the order of the day: ‘Discipline’ could be the soundtrack to Bandersnatch, and the dub-driven ‘A New Love Song’ is desolate but beautiful.

Introspective (the title is a reference to the mind rather than physical structures) but cathartic, Architecture is an incredibly polished debut, and should herald a new player in the indie rock game.

Hightown Pirates - All Of The Above

Some bands just fall through the cracks.

Our favourite industry isn’t fair, nor does it make any promises. Countless acts of considerable pedigree, even with successful back catalogues under other names, often fail to make an impact: The Shining were a supergroup formed in the early part of the century, consisting of ex-members of The Verve and briefly John Squire, but did little damage. John Frusciante can’t get himself arrested outside of Red Hot Chili Peppers but is considered a vital cog in their wheel, hence his hokey-cokey relationship with the band (at time of writing, he’s a full-time member again).

Hightown Pirates have a similar problem. The credits on this second long player include musicians who have been in Babyshambles, Gorillaz and Shack. The mastermind behind the band, Simon Mason, exists in Britpop folklore, but also has a lauded debut album from 2017 under his name. And yet, Mason often, understandably, vents frustrations that his band are never asked to appear at festivals or even tour, and get virtually no recognition in the media. Yet it doesn’t deter him – demonstrable evidence that it’s a labour of love, not just a career.

On listening to All Of The Above, the lack of acknowledgement for Hightown Pirates is both a mystery and a shame, as there is much to admire here. The musicianship is exceptional: melodic yet noisy guitars, flexible bass-lines, soulful backing vocals, all cushioned by a persistent backdrop of northern soul brass. The ingredients may sound familiar, and Mason freely admits that it’s not notable for its originality, but this doesn’t detract from the talent.

The main touchstone is Paul Weller, not least because of Mason’s unerringly similar voice. ‘He Who Lies Flat’ is all life-affirming chords following a lengthy instrumental opening, the brass section front and centre. The deft touch of single ‘Girl From The Library’ sounds like an off-cut from Stanley Road, while on the acoustic ‘Different Drums’ he even cribs from The Jam’s ‘English Rose’ as a nice tribute. Once again, Mason isn’t so blind to not see where the comparisons are, so acknowledges them head on.

Lyrically, Mason often rails against the usual (but deserved) suspects; those that took the 2016 referendum as a mandate to do whatever they wanted (‘the Island Monkeys screaming so excited, as the kingdom falls on its sword that’s what we decided’). Otherwise he mainly acts as storyteller: ‘Girl In The Library’ is a metaphor for encountering several of life’s characters as they pass through, while ‘A Sunday Sermon’ is a wistful and sad tale of a ‘leading lady’ and a soldier as they too look at life’s roller coaster.

Simon Mason’s stance is that Hightown Pirates offer hope and salvation through music, and he speaks from experience. In these desperate times such reminders are most welcome.

Brendan Benson - Dear Life

It’s fair to say that domestic bliss doesn’t make for the most beguiling of musical subject matters – which is ironic as, broadly speaking, it’s the one thing we all have in common.

Since forming The Raconteurs with the Jacks White and Lawrence, and Patrick Keeler (the rhythm section of The Greenhornes), Brendan Benson has been an advocate of the small pleasures enabled by the quiet life. In a 2009 interview he extolled the virtues of cutting the grass (‘as satisfying as writing a song. More, sometimes.’), and his three solo albums in that period have all, to a lesser or greater extent, outlined such contentment.

There’s more of the same on Dear Life, and whilst his seventh solo album is being sold as a sonic departure, it’s actually business as usual.

This is apparent with even a cursory look at the tracklist: ‘Richest Man Alive’ (‘I got two beautiful babies and one hell of a good-looking wife’) rollicks along and therefore saves itself from being too mawkish, while ‘I’m In Love’ is repetitive lyrically in its 90 seconds but features moody chords that belie the subject matter.

It may seem obvious to reference The Raconteurs but seeing as they were largely responsible for Benson’s crossover it’s also valid, and Dear Life also acts well as a signpost for who does what: ‘Half A Boy (Half A Man)’ features familiar guitar with a daytime radio friendly, big chorus, although with a more spindly beat. But you can practically hear Jack White on backing vocals, and the album as a whole demonstrates that Benson is the dominant force in that band.

The heavy drumming and brass section on the freewheeling ‘Baby’s Eyes’ also bring to mind the supergroup’s instincts to go unashamedly Travelling Wilbury. The title-track features heavy brass too, but that only adds misleading cheer to a narrative about battling depression, one of a handful of references to the darker side of ‘normal’ life.

Of the new sounds that are being promoted, only four tracks deviate from Benson’s tried and tested swaggering rock formula. The taut opener ‘I Can If You Want Me To’ features an increased BPM via electronica but swiftly reverts to type with an explosive guitar-driven chorus comprising simply the title line. ‘Good To Be Alive’ sounds like Beck’s recent output as his voice gets auto-tuned but retains the familiar topsy-turvy melody he’s so fond of. ‘I Quit’ melds some new grooves against a traditional acoustic sound, and lastly the dramatic closer ‘Who’s Gonna Love You’ has snappy beats and effects and also a sample of what are, presumably, his children.

Kudos for at least nudging the boat out, but the best track on the album is also the simplest: ‘Freak Out’ does exactly what it says on the tin, a fast-paced rocker akin to a slice from the Nuggets series with a jabbing guitar solo, the opportunity to let loose in the studio grabbed with both hands.

By Brendan Benson’s standards this is a modernist album, blessed with brevity and playfulness whilst still wearing his heart on his sleeve. And it’s always fun.

King Charles - Out Of My Mind

This is likely to be the most unsurprising statement you’ll ever read but…sex sells.

It’s the truest adage of commercialism, and also the oldest. And brace yourselves ladies and gentlemen, because King Charles – who used to harness a sound lazily pigeon-holed as ‘folky psychedelia’ – is feeling sexy. Or he’s feeling skint. On Out Of My Mind it’s hard to tell which.

His last album, Gamble For A Rose of 2016, added some guitar-shaped muscle to the whimsy of his debut, but didn’t really take it up to the next level. So, as sure as eggs is eggs, a volte-face has been performed and we now have a much poppier record. It’s easy for a reviewer to be dismissive when this happens (because it’s very likely to have been a conscious decision), but we must remember that, like all of us, musicians have bills to pay.

And it’s fine for what it is. There are some gems contained within; ‘Deeper Love’ is cut from the same cloth as Prince, attitude-pop held together by a throbbing bassline, liberally dashed with finger clicks and gospel choir. ‘Feel These Heavy Times’ floats with summery abandon, a jaunty sea shanty with infectious positivity while the slinky, laconic funk of ‘Freak’ soulfully shimmers from the speakers.

But it’s the preoccupation of matters carnal which drag the album down, and sadly that’s broadly the concept: the title-track feels pensive with bluesy guitars that add to the drama, but are let down by Charles Costa’s voice, breathing into the ear, ‘I want to feel your lightning strike’. ‘She’s A Freak’ goes one step further (‘you’ll be coming all night’) while the bouncing beat and chiming keys of ‘Drive All Night can’t hide his avarice.

Worst of all is ‘Money Is God’, which has to be ironic if King Charles has any sense. Like the worst of arrogant 2000s R&B records it opens with a cod-air hostess spoken introduction before breathy female vocals hide the lack of real structure. If it is a parody of all those misogynistic offerings (and let’s give it the benefit of the doubt), then it’s unerringly close to the real thing.

On the occasions when he eases away from matters coitus, the luxurious production serves the songs well. ‘Melancholy Julia’ recalls his roots, aping Mumford & Sons in its earnestness and throwing in some Johnny Buckland guitar licks, although it doesn’t burst into life despite continually threatening to do so. Meanwhile, ‘Watchman’ stands out from the rest of the album, all poodle rock guitars and melodrama once again channeling Prince but on his more mainstream offerings.

Out Of My Mind has several things working in its favour: as noted, the production is first class, and vocally King Charles pushes himself bravely where his contemporaries wouldn’t dare to tread. Musically, there’s huge amounts of variation and expertise on show, and recounts of his emotional, physical and mental recovery from a skiing accident in 2010. At points it just feels a bit too tacky.